When I decided to make Gotogra a lane-based game, I knew the lanes had to matter. I didn’t want the three-lane setup to just be cosmetic or spatial flavor — I wanted each lane to carry meaning and potential.

That’s where lane buffs came in: they give the battlefield tactical identity, and they give enemies a flexible way to scale alongside the player’s growing power. Much like Marvel Snap or early versions of Gwent, I wanted each space to feel like it had its own tension — whether it’s a benefit to stand still or a trap waiting to happen.

Two games that really demonstrate the power of lane-based systems are Marvel Snap and Gwent. In Marvel Snap, each lane has a randomly assigned rule that reshapes your strategy every match. Players have to adapt constantly, deciding where to commit their limited turns and cards in the face of shifting lane conditions. Keith Burgun wrote a great breakdown of this in his article: Marvel Snap is a Testament to the Power of Ruleset Design.

Gwent, particularly in its earlier iterations, used two distinct lanes — melee and ranged — which limited card placement and introduced environmental effects like weather that applied lane-wide. This forced players to weigh positioning, spreading their units, or risking clustered vulnerabilities. There’s a great overview of these mechanics and lessons learned in this article from Nerdlab: Gwent: 5 Exceptional Design Choices.

These games helped reinforce an idea I kept coming back to during Gotogra’s design: if you’re going to divide a battlefield into lanes, each one should matter — strategically, emotionally, and mechanically.

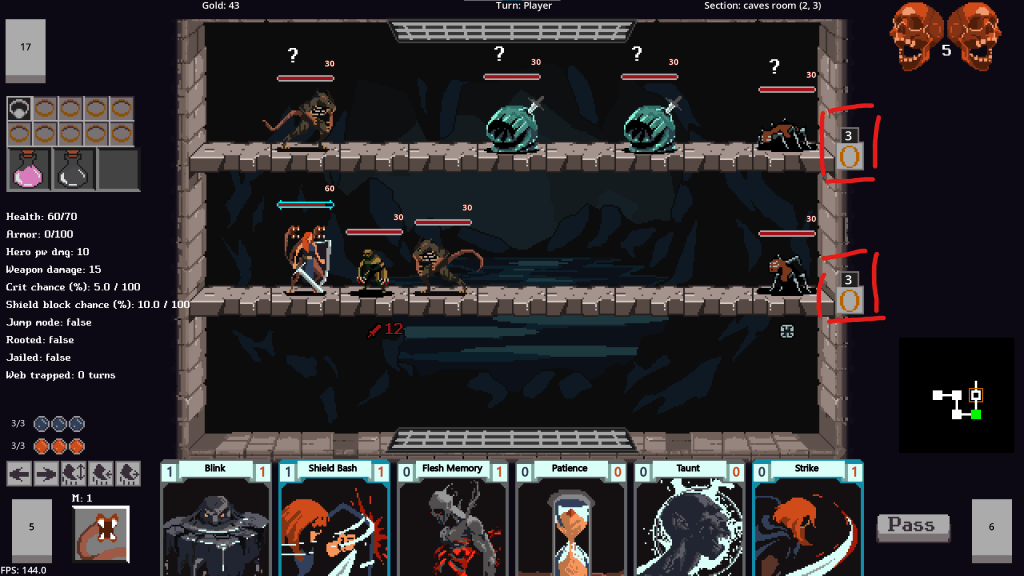

Before going deeper into Gotogra’s lane buffs, I want to clarify something that could cause confusion: although Gotogra has a lane-based system, it’s not a traditional grid-based tactics game. At most, there are three vertical lanes, but each one is designed to carry strategic weight and provide distinct interaction opportunities.

The player’s character can jump between platforms within the same lane by spending 2 energy. Movement within a lane is flexible: the player can leap up to 6 platforms forward or backward, as long as the target platform is unoccupied. However, changing lanes is more constrained — you can only move to the directly adjacent lane (up or down from your current platform), and it still costs 2 energy.

This movement system means that even with only three lanes, positioning and decision-making are far from trivial. The rules are simple, but the implications — especially when lane buffs and enemy behaviors come into play — are rich and layered.

So what exactly is a lane buff in Gotogra?

A lane buff is a persistent effect tied to a specific lane. Once triggered, it applies powerful upgrades to all enemies currently occupying that lane. These buffs come in various forms — some grant a one-time damage immunity shield, others increase enemy damage or armor, and more exotic ones apply unique hazards. One of the most dangerous is internally referred to as “deadly traps.” While not literally lethal, this effect causes highly damaging traps to spawn on every platform within the lane when its countdown expires.

Deadly traps are particularly interesting because they only activate after the lane has been cleared of enemies. This was an intentional design decision: I wanted to discourage the player from stalling the game by cycling through their deck in a safe, empty lane. They can still do that — but only for a few turns before the lane becomes a danger zone.

This ties into player agency: the player must constantly evaluate whether to stay in a lane to benefit from a safer position or move out to deny enemies the opportunity to claim a lane buff that could tip the balance of the room. Good decision-making isn’t just about surviving the next turn — it’s about anticipating how the battlefield might evolve two or three turns ahead.

Lane buffs in Gotogra aren’t just a layer of difficulty — they’re a response to how players grow. As the player scales through cards, rings, and other upgrades, lane buffs ensure that enemies can keep up in ways that are contextual, dynamic, and fair.

I’m also toying with the idea of introducing a version of lane buffs that benefits the player. The concept would be that these buffs aren’t passive or random but come from cards the player can install during combat. It’s still early thinking — and could definitely risk creeping the game’s scope — but on paper it sounds promising. It opens up exciting design space not only for new player cards but also for new enemies that interact specifically with these player-controlled buffs.

Thanks for reading! If you’ve made it this far, I appreciate your interest and curiosity. Designing Gotogra has been a constant process of trial, error, and discovery — and systems like lane buffs are a small window into how much goes into making even simple mechanics feel meaningful.

Leave a comment